I know what you are all thinking, “Why hasn’t anyone written a history of the Compromise of 1850?” Well, your heart’s desire has been granted. Fergus Bordewich’s America’s Great Debate is just such a book. For those of you who are not US history teachers or 19th century political history junkies, the Compromise of 1850 was a massive political compromise that settled, albeit only temporarily, the issue of the expansion of slavery into the western territories of the United States which threatened to cause a civil war. Why does this even matter? Bordewich makes the arguments that, on the one hand, the Compromise of 1850 is largely overshadowed by the Civil War that broke out 10 years later, while on the other, it did actually walk the nation back from the brink of war in 1850. This is no small matter for all the parties involved: pro-slavery, free staters, abolitionists, and those who just wanted to ignore the issue of slavery, were so set in their views that no one thought it even possible that a resolution could be reached. He also argues (somewhat less convincingly) that this compromise has relevance today as a model for our political gridlock.

I know what you are all thinking, “Why hasn’t anyone written a history of the Compromise of 1850?” Well, your heart’s desire has been granted. Fergus Bordewich’s America’s Great Debate is just such a book. For those of you who are not US history teachers or 19th century political history junkies, the Compromise of 1850 was a massive political compromise that settled, albeit only temporarily, the issue of the expansion of slavery into the western territories of the United States which threatened to cause a civil war. Why does this even matter? Bordewich makes the arguments that, on the one hand, the Compromise of 1850 is largely overshadowed by the Civil War that broke out 10 years later, while on the other, it did actually walk the nation back from the brink of war in 1850. This is no small matter for all the parties involved: pro-slavery, free staters, abolitionists, and those who just wanted to ignore the issue of slavery, were so set in their views that no one thought it even possible that a resolution could be reached. He also argues (somewhat less convincingly) that this compromise has relevance today as a model for our political gridlock.

Bordewich does an excellent job of breaking down the minutia of early 19th century politics. Explaining things like the party system. There is no GOP. The major parties are the Whigs and the Democrats and what they represent is extremely complex and often changes by region. He also breaks down how politics was even done. Politicians in the early 19th century had a celebrity status they lack today and politics was a spectator sport. Politicians were expected to be able to give speeches that lasted hours with few if any notes. Constituents were not phased by negativity or mud slinging as it was a sign that their politicians were fighting as hard as they could for them. The public could simply wander onto the floor of the house and senate and talk to their representatives. At the same time it was considered unseemly for presidential candidates to do too much campaigning.

The other really great thing about this book is it looks at the larger issues leading up to the compromise and its larger outcomes. Bordewich doesn’t just strand the reader in Washington DC, but takes you out into the territories in the Southwest and California and shows how those regions tried to work out their own futures, sometimes at great peril. New Mexico for example wanted to be admitted to the Union as a free state and declared as much. However, Texas felt that New Mexico should a) be part of Texas and b) allow slavery so they attempted to annex it a couple of times by force. He also draws very focused pictures of the players. There is Henry Clay, known as the Great Compromise for his skill at walking the government back from various political crises. Stephen Douglas, a rising political star trying to make the issue of slavery simply disappear. John C Calhoun, a southern firebrand bound and determined to spread slavery all over the United States. Brodewich does an excellent job of making them accessible to modern readers.

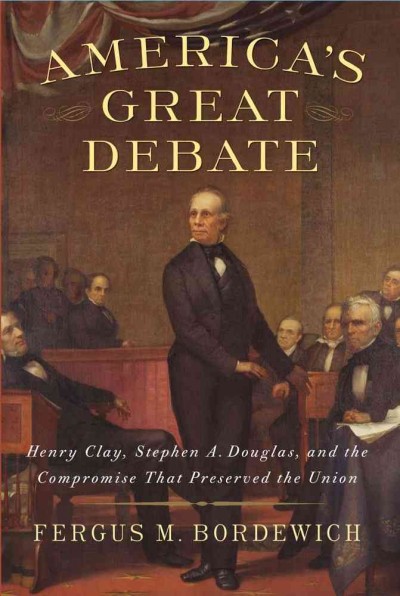

The book, I think, does suffer from both its title and its cover. I think too many people read America’s Great Debate and think “boring politics from the 19th century”. Politics in the 19th century wasn’t boring and the issues permeate every level of society, making the story more about the United States in 1850 than just the politics around the compromise. This view – “boring politics” – is reinforced by the cover, which is a picture of Henry Clay speaking before the senate. I think a better title would be 1850: The Civil War That Wasn’t, and a cover with a map of the western territories. In short, anyone interested in the history of the Civil War or early American history in general will enjoy this book.